How can design contribute to heritage practices in military conflicts?

Ruin in Reverse is a design inquiry on cultural heritage and human rights in military conflicts. It aims to critically reflect on the potential of design practice to contribute in this issue and to challenge the boundaries between design, art, archaeology and anthropology in relation to heritage practices.

The project was developed under an experimental process that connects material exploration to theoretical research. The materiality of 'the rubble', from depiction on media to reconstruction and reproduction, was explored through design processes and design tools such as 3D scanning and 3D printing, for example.

Rubble Image

What do these pictures do with us?

These images can shock us. But they don’t help us much to understand. These photos frame our understanding of war.

By framing, they exclude. They can represent the results of destruction but cannot articulate its causes.

Are we merely voyeurs?

The Syrian war has being covered in real time by cell phones, twitter feeds, maps that remind games. But all these materials have been spread through internet without historical context.

The lack of context and the massive exposure increased by the digital era make the reality becomes less real.

The representation becomes a spectacle.

“The awareness of the suffering that accumulate in wars happening elsewhere is something constructed.

It flares up, it is shared by many people and fades from view.”

susan sontag

It creates sympathy and it shrivel sympathy. An abstract feeling of compassion is all that remains.

How to make this construction to be remembered by its context and its comprehension? How to make this construction to not fade? How those who haven’t experienced the reality of war can understand the pain

of the others?

WHERE IS THIS PLACE? How many times have you seen this place? How many images of this non-place have you seen before? These images construct an idea of generalization to those places, an idea of displacement, de-identification and, therefore, dehumanization.

Construction

Constructing this rubble scenario was an attempt to create a concrete relationship between me and the image of this “displace”. To set up a dialog between my body and the materiality of the rubble where a different way of thinking could happen.

Moreover, by constructing the rubble scenario out of debris of a demolished building in Sweden and ceramic pieces discarded in design process in HDK, I established a connection between that displaced image of Syria and the place where the project happened: Gothenburg and HDK.

Origin of the material used to construct the rubble.

Mapping

After the rubble construction, a process of mapping was established. The aim was to get all the information necessary to be able to reconstruct the same pile of rubble after its deconstruction.

In order to map the rubble, 3D models and a top view image with grid were developed to help in the reconstruction process. Two cameras were settled to film the whole process of deconstruction.

3D model of the rubble made with the photogrammetry software Autodesk ReMake

Deconstruction

I borrow Tim Ingold’s concept of making to explain why the process I went through might be relevant to the design practice. It was a “process of growth”. It means to put myself since the beginning as a participant in what he calls “a world of active materials”.

In the process of making, I “join forces” with the materials, “bringing them together or splitting them apart, synthesising and distilling, in anticipation of what might emerge.”1

1. Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, (London: New York: Routledge, 2013)

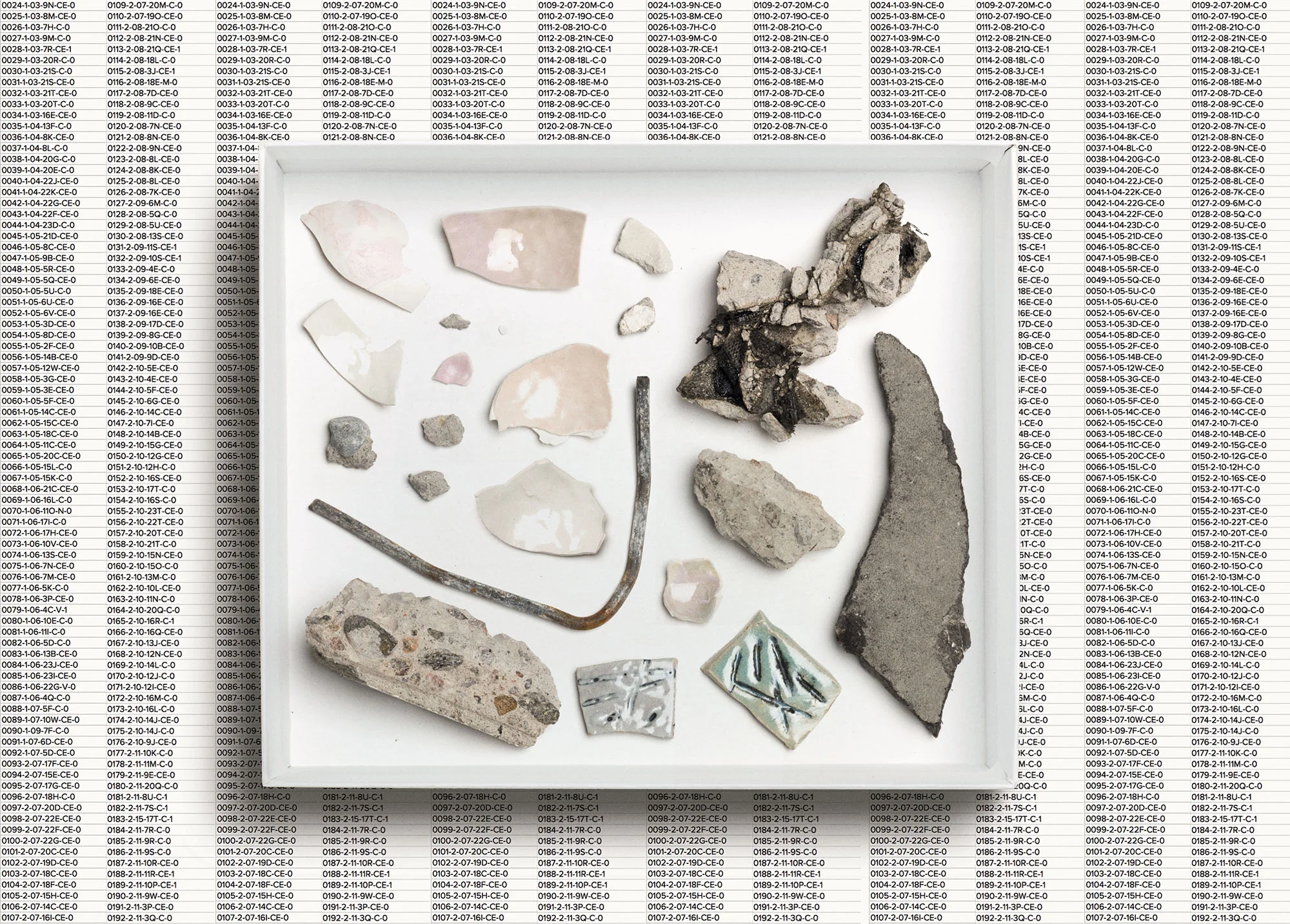

1442 pieces, 8 layers

8 layers - top view images 3D models

If the rubble was seen through a satellite image, it will be represented by 4 pixels.

If this rubble was seen through a satellite image, it will be represented by 4 pixels. In satellite images, a single color pixel represents 50 cm of surface area. This resolution defined by international regulations allows part of buildings to be identified and to be analysed in an architectural perpective. Eyal Weizman compares this analysis with “an act of archeology of the present”. “An architectural reconstruction based on an analysis of images and the ways these images are composed in pixels”.

Before and after satellite images of destructed sites has been used by human rights institutions as main evidences of war crimes. However, the 50cm per pixel resolution is not enough to show people and the human are excluded of the evidence. Besides, with the increase of the algorithmic process of data representation instead of people for viewing those images, the human is being even more excluded. According to Weizman, the human rights analysis entered in a post-human phase. 2

2. Eyal Weizman, Before and After: Documenting the Architecture of Disaster (Strelka Press,2014)

“[...] to intentionally direct an attack against historic monuments and buildings dedicated to religion constitutes a war crime [...]”

fatou Bensouda

For the first time, the International Criminal Court of the Hague convicted a man as a war criminal based only in cultural property destruction. Al Mahdi planned and executed the destruction of the mausoleums of Timbuktu in Mali, a heritage site inscribed in UNESCO’s list.

On one hand there was good reactions by the cultural heritage professionals because it highlights the importance of cultural heritage for humanity. On the other hand, human rights advocates were concerned that the crimes of rape, torture and murder of citizens of Mali by the same man was not investigated by the court.

One might have the impression that human lives are less valuable than buildings and artifacts. But the issue regarding cultural heritage and human rights goes beyond the court in the Hague. The essay Cultural Heritage and Human Rights: a Holistic Approach Beyond the Hague is part of this project and reflects on this issue.

“the decision of the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a landmark in gaining recognition for the importance of heritage for humanity as a whole and for the communities that have preserved it over the centuries”

Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO

“while this case breaks new ground for the ICC, we must not lose sight of the need to ensure accountability for other crimes under international law”

Erica Bussey, the Amnesty International's Senior Legal Advisor for Africa

Archiving & Cataloging

Each of the 1442 pieces was catalogued by taking pictures of each one separately and by developing a code system to identify them.

“The way in which museums have classified objects and the connection between cataloguing objects and people is in itself a power issue. We cannot go on doing things the way they have been done without asking ourselves what ideology we are reproducing with these routines. Working with collections must be a dynamic process, including many voices and diverse knowledge, without ranking.”

Adriana Muñoz, curator of the World Culture Museum in Gothenburg

According to Adriana Muñoz, the creation of World Culture Museum in Gothenburg had the idea that non-european objects could help in the integration of non-european immigrants. This idea however reinforces the dichotomy between we and the others, a concept that have been guiding cultural heritage discourse and practices around collecting, labelling, classifying, interpreting and exhibiting material that tell stories about people.3 This dichotomy, known as well as clash-of-civilization argument, is a dangerous and superficial argument that “sees separated and self-contained areas in the world rather than their intertwined histories”. Indeed, this contrast between “our values” and “their values” is related to the destruction of cultural heritage and also to the war itself.4

The narrative that framed the destruction of Palmyra and Mosul, for instance, were simplified by this dichotomy: the international community protecting “universal values” in one side and the “Islamic world” destroying them in the other.5

To criticize meaningfully the destruction of cultural heritage in Syria, Iraq and anywhere, it is necessary first to criticize the institutions and the criteria used in cultural heritage practice. Because these criteria have been “constructed along with the same geopolitical favoritisms and [...] by the same state apparatus that leads to war”.6

3. Adriana Muñoz, From Curiosa to World Culture. The History of the Latin American Collections at the Museum of World Culture in Sweden, (Gothenburg: Department of Historical Studies, University of Gothenburg, 2011)

4. Esra Akcan, 'Modernity as Perpetual War or Perpetual Peace?', Aggregate, http://we-aggregate.org/piece/modernity-as-perpetual-war-or-perpetualpeace

5. Pamela Karimi and Nasser Rabbat,'The Demise and Afterlife of Artifacts', Aggregate, http://we-aggregate.org/piece/the-demise-and-afterlife-of-artifacts

6. Esra Akcan

Reconstruction

The reconstruction process started with the development of instructions to do it. Using the code system, the images of isolated pieces and the 3D models of each layer, maps were developed and the printed versions of these maps can be used to locate, to identify and to position each piece.

Or an animated version can be project in real size over the wood board and guide the performance to position every piece in its original place.

However, it will be never the original rubble.

Even if it was possible to position every grain of dust of this rubble as it was before, the new context, the new players, the new movements, will make it different. And every time that it was reconstructed it would be another version.

But can one said that the first one, the one constructed on 15th November 2016 is the original one? Or was it already a version of the newspaper cover? Aren’t these maps and animation many versions of the rubble?

30 maps to reposition each of the 1442 pieces

“What are the many versions if not diverse perspectives of a movable event?”

Oliver Laric

Can one said that authenticity is decided by the viewer?

Is the Palmyra ruins after the destruction by ISIS just another version of the ruins that have been changing since its construction?

Should we physically rebuild Palmyra? Or its many versions are already a reconstruction process?

There are meaningful and valuable ways to give an afterlife to destroyed landscapes through the representation of its destruction. These representations “demonstrate that in many cases, destruction is less an end-point […] than the beginning of a process of meaning-making”.7

Therefore, the absence of a monument does not mean it will be lost or forgotten but rather than its existence could be defined, for instance, through a “specific mode of image production”.8

Once the monument’s “potential for destruction” begins to function as “the most meaningful aspect of the monument’s existence as an object”, then its destruction becomes its realization.9

7. Keith Bresnahan and J. M. Mancini, 'Introduction' in Architecture and Armed Confict ed. JoAnne Mancini and Keith Bresnahan (Taylor and Francis, 2014)

8. Thomas Stubblefeld, 'Iconoclasm beyond Negation: Globalization and Image Production in Mosul', Aggregate, http://we-aggregate.org/piece/iconoclasm-beyond-negation-globalization-and-image-production-in-mosul

9. Keith Bresnahan and J. M. Mancini

Reproduction

Regarding the reproduction of destroyed buildings and artifacts, 3D printing technology has opened up a lot of new possibilities.

Original and 3D printed - piece #0012

3D printed and original - piece #0297

Original and 3D printed - piece #1196

3D models of the 8 layers made with photogrammetry software

Reproduction of

the Arc of Palmyra

The Institute for Digital Archaeology, based in UK, has been challenging ISIS by reproducing replicas through 3D printing. To produce 3D models of cultural heritage sites at-risk, they have distributed 3D cameras to volunteers in Middle East and North Africa. Their goal is to gather one million 3-D images of sites in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, Iran and Yemen.

They have created a 3D model of the arc of Palmyra, which was assembled in London’s Trafalgar Square. As the institute’s director, Roger Michel, said, “it is really a political statement [...] we are saying to them, if you destroy something we can rebuild it again.”

Should we be aware to do not make the same mistakes by “labelling” these data, it means, by giving a one-dimensional meaning to those places, like it has been doing in ethnological museums for instance?

By “challenging” ISIS with the 3D printed Palmyra arch in London city centre, are we not reinforcing the dichotomy between we and the other? As designers who work with curation, exhibition, restoration and digital heritage, we must be aware of our responsibilities regarding this issue.

After the unveiling of the 3D printed arch in Trafalgar Square, Joseph Willits of the Council for Arab-British Understanding expressed his concern: “While the digitally created replica of Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph looked glorious in the London sunshine,

I cannot help but feel this project plays a role in cementing the idea that Syria’s monuments and heritage are far more important than its people.”

Indeed, isn’t it a contradiction to mourn the destruction of Palmyra but not the destruction of Syrian villages?